NASA announced they need at least $1.6 billion in additional funding in order to meet the 2024 deadline for sending another manned mission to the moon.

Dubbed Artemis, the programme was originally slated for a 2028 landing as part of the Space Policy Director 1, signed by President Trump in 2017. Artemis incidentally is the Greek Goddess of the Hunt and the Moon.

However, in March 2019 Vice President Pence announced that the timeline would be moved up to 2024.

Although many claim the timetable shift was politically motivated, for NASA it presents a number of technical headaches.

For one thing, NASA hates risk. Space travel is fraught with danger as the slightest mishap can cause everything from the mission being scrubbed to the death of the crew.

Then there’s the launch. Despite their use of large, powerful rockets, NASA doesn’t like fire very much either. Fire is bad and goes to extraordinary lengths to make sure nothing gets hot, sparks or can burn in the first place.

This takes time and money and chopping 4 years off the launch date puts scientists and engineers under a great deal of pressure.

The end of the Space Shuttle Programme effectively brought to a close NASA making its own hardware. Increasingly the space agency has relied on the Russians and private contractors like SpaceX to ferry personnel, equipment and hardware into space.

NASA now have to deliver the Space Launch System in fraction of the time. The multibillion-dollar launcher has been in development since 2011 and has been plagued by setbacks and ballooning costs ever since.

Pence’s address, in which he slashed the moon landing deadline, made it clear that the administration would no longer tolerate delays and partners would be shed if needs be. That’s bad news for Boeing.

In order to meet the 2024 deadline, the SLS may have to be abandoned – or at least paused – in favour of using commercial rockets.

Specifically, Space X’s Super Heavy.

If NASA were to switch suppliers, it would be a heavy blow to Boeing’s reputation and likely their share prices. Not to mention the end of an 8-year investment that many saw as nothing more than an agency wide jobs programme.

With the inaugural launch slated for 2018 and now looking more like 2020 it’s questionable whether or not Administrator Jim Bridenstine can continue to back the SLS. Especially considering the truncated time frame.

Officially NASA remains confident the SLS can be delivered for 2024. But time pressures and the inherent risks associated with rushing anything to do with space travel may force NASA’s hand. Especially if Space X successfully launch their Super Heavy (formally the BFR) in 2020 as planned.

Then they have to deliver Orion – the crew capsule that will ferry the astronauts into space. This too has been in development since 2004, when President George W Bush unveiled his Vision for Space Exploration.

Built in partnership between Lockheed Martin and Airbus (and backed by the ESA) the Orion was originally intended to ferry crew and supplies to the ISS but has since had its operational remit widened to include the moon landing.

Although now Amazon has thrown its hat into the ring with the Blue Origin lander that boasts capacity to carry 6.4 tonnes of supplies to the surface, it really could be anyone’s game at this point.

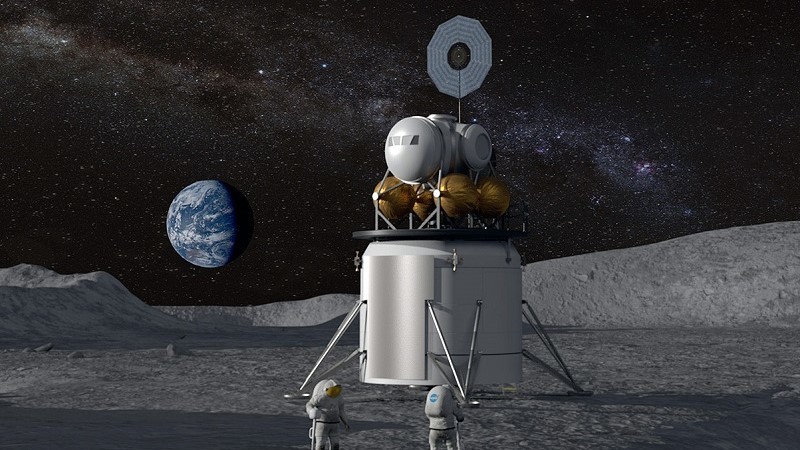

Finally, the Gateway needs to be constructed.

The Gateway is a secondary space station in orbit around the moon. It will serve as a staging ground for manned and unmanned missions to the lunar surface. It could also be a precursor to lunar colonisation.

Regardless, it represents a way to reduce the cost and risks associated with landing objects on the moon. If successful it could also serve as an operational template for manned missions to Mars.

But it doesn’t address one of the biggest challenges facing humanity’s ongoing endeavours in space exploration.

Since the very first attempts to turn us into a space faring species, we have relied on rocketry to get into space. Burning propellant to break free of both the atmosphere and gravity.

Then there’s fuel on board the craft for the two-way trip which – if burned too quickly can prevent the success of the mission. And doom the crew to a very cold, unpleasant fate in the void.

For the time being it's unlikely we can do anything about launching craft or materials into space using a rocket.

It’s hardly Star Trek but it works.

With Space X achieving success with reusable rockets, the cost of launch can in theory decrease over time too.

But what about when the module or craft is actually in space?

Fuel capacity is low meaning that modules have to essentially line themselves up with their intended target, burn fuel and hope for the best. The margin for error is incredibly slight.

In the case of sending a manned mission to the moon, it’s like throwing a dart and hitting the bullseye from the other side of the room.

With your off hand.

However, alternatives are in development that could make interstellar travel entirely more feasible, avoiding the need for fuel altogether beyond the fuel used by the Reaction Control Systems.

The EM Drive was discovered by accident and uses no fuel whatsoever.

It works by bouncing microwaves around a cone shape cavity. It defies laws of physics and recent test in Germany question the engine’s ability to function at all.

However, if the engine does prove functional then it could represent a means to propel humans through the stars without the need for fuel.

If it actually works, it would require relatively little energy so could be powered by solar cells, making space travel incredibly efficient.

Currently the future of the EM Drive is in doubt as the recent tests suggest that the thrust created by the drive is being caused by the Earths’ electromagnetic field.

Critics claim that the tests weren’t through enough as the outputs tried were so low that interference would have drowned out any positive results.

Moreover, without a mu metal shield it’s impossible to determine if the Earth’s electromagnetic field is responsible.

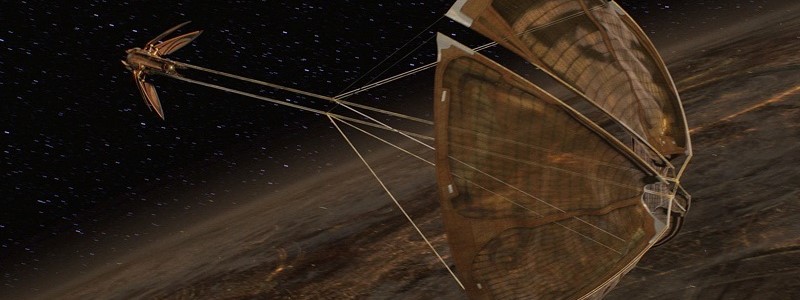

The idea of solar sails has been toyed with by science fiction writers for years. Star Wars and Star Trek have both depicted craft that harness photons in order to propel ships through space.

While light has no mass, it has momentum which can be passed on to other objects. The solar sail effectively captures the light and with it the momentum, driving the ship forward.

Again, solar sails don’t require fuel of any kind. Just a big enough sails to catch enough rays to push the craft forward.

The LightSail 2 built by The Planetary Society will launch in June 2019. The cubesat will deploy its sail – roughly the size of a boxing ring - and attempt to orbit the Earth using nothing but harnessed light particles.

If success it’ll be a historic moment and could provide NASA and other organisations, the answer to the long-standing challenge of how to travel the vast distances of space without – effectively – bringing a fuel truck along for the ride.

Whether the EM Drive or the LightSail 2 works is almost incidental. The concepts highlight the need and the desire to devise a means of propulsion that doesn’t require carrying vast amounts of fuel. Or requires fire or radiation.

We’re still a long way off impulse engines, warp drive or hyperspace but it’s a step in the right direction towards sustain space flight. Which opens huge potential in terms of exploring our solar system and beyond.

KDC Resource are expert recruiters for technical and engineering talent for the space sector. If you’re looking for your next opportunity, then register your details.

Or if you’d like to work with us on your requirements, get in touch today and a member of the team will help.